Published: Apr 6, 2019 by Chloe

The field of neuroscience is currently facing the possibility of a re-revolution about adult human hippocampal neurogenesis. Throughout most of the lifespan of the field, it was thought that no new neurons are born in adulthood following developmental periods of neurogenesis in prenatal and early postnatal life. In the words of Santiago Ramón y Cajal: “Once the development was ended, the founts of growth and regeneration of the axons and dendrites dried up irrevocably. In the adult centers, the nerve paths are something fixed, ended, and immutable. Everything may die, nothing may be regenerated. It is for the science of the future to change, if possible, this harsh decree.”

In the 1960s and 1970s, scientists Joseph Altman and Michael Kaplan challenged this “harsh decree.” They used an early marker of DNA synthesis, 3H-thymidine, which can detect DNA replication during cell division (“S phase”) and thus label cells that have newly divided, or been born, from progenitor cells. 3H-thymidine is a radioactive form of thymidine, the DNA nucleoside “T”. 3H-thymidine is incorporated into newly synthesized DNA strands in addition to non-radioactive thymidine, making the newly synthesized DNA visible. This labeling technique revealed evidence for neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus (DG) of the hippocampus (among some other regions) of many mammals. In the 1990s, 5-bromo-3-deoxyuridin (BrdU), a thymidine analog, was developed to label cells in S phase with more specificity when combined with co-labeling techniques. This technological advancement produced more evidence of adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, this time in humans as well. The weight of this evidence was sufficient to overturn the standing view that no new neurons were born in adulthood, and the paradigm shifted.

Last year, two publications came out back-to-back in high-profile journals; one (Sorrells et al., Nature) did not find evidence for adult hippocampal neurogenesis (AHN) in humans while the other (Boldrini et al, Cell Stem Cell) did. A recent paper (Moreno-Jiménez et al., Nature Medicine) also finds evidence for human AHN. These inconclusive and contradictory articles have re-ignited the debate about adult human hippocampal neurogenesis. Of note, there seems to still be an agreeable consensus that neurogenesis occurs in adult rodents, as described below:

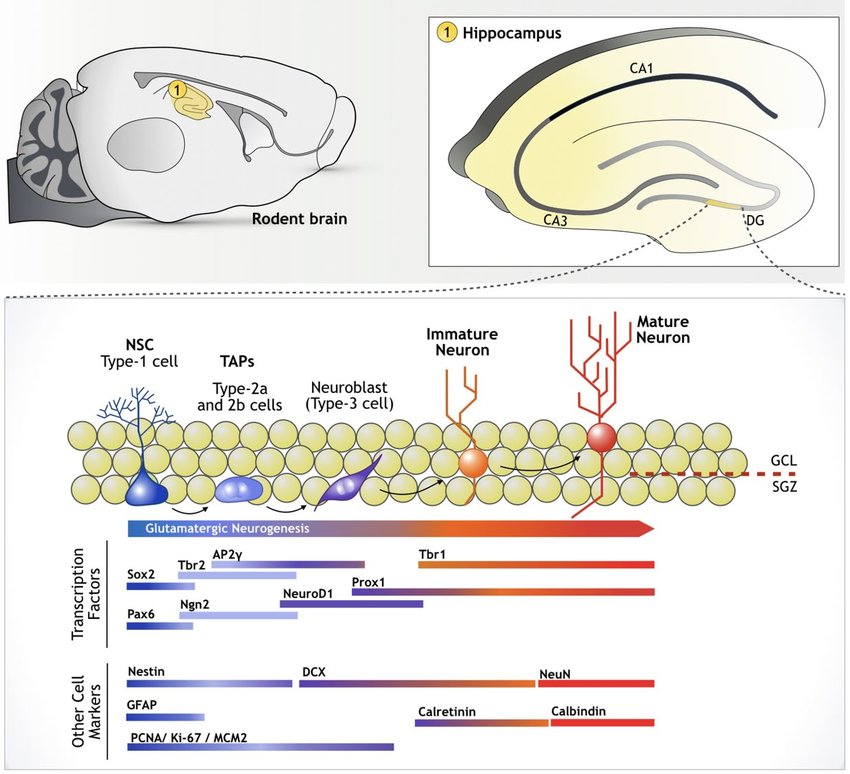

This image is a simplified pictoral description of the process of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, including which markers are expressed during which maturational stage (source).

Boldrini et al. verbalize the process of neurogenesis as follows:

- Generation of new neurons starts with quiescent radial-glia-like type I neural progenitor cells (QNPs) expressing GFAP, SOX2, BLBP, and/or nestin

- QNPs being expressing Ki-67 and lose their quiescent status, generating amplifying, type II, intermediate neural progenitors (INPs) expressing Ki-67 and nestin

- INPs differentiate into neuroblasts, or type III INPs, and lose expression of SOX2 and GFAP and gain expression of DCX and PSA-NCAM

- As neurons mature they express NeuN, Prox-1, calbindin, and betaIII-tubulin

Not all markers in the papers discussed are included in the above figure. Some additional key markers are summarized in the table below.

| Marker | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BLBP (brain lipid binding protein) | labels neural stem and progenitor cells | may be present in some parts of the adult brain? |

| BrdU | dividing cells | labels cells in S phase specifically |

| calbindin (CB) | mature neurons | also a marker of a subtype of inhibitory interneuron |

| calretinin (CR) | immature neurons | also a marker of a subytpe of inhibitory interneuron |

| Doublecortin (DCX) | immature neurons | expressed at low levels in oligodendrocytes and microglia |

| Ki-67 | dividing cells | Ki-67 expression means not in G0 (G0 = not dividing), but may pick up some cells in G0 and may not pick up all cells that are not in G0 |

| Nestin | neural stem/progenitor cells | intermediate filament protein; downregulated upon differentiation |

| NeuN | mature neurons | does not recognize all neuronal cell types |

| PSA-NCAM | intermediate neural progenitors | sole expression cannot be indicative of immature neuron phenotype; must co-localize with something like DCX; also expressed in a subpopulation of mature interneurons |

| SOX | neural progenitors | family of transcription factors; SOX2 also expressed in dividing glia |

Sorrells et al.

Cells that expressed markers of cell division (Ki-67, SOX1 and 2) and immature neurons (DCX and PSA-NCAM) were found to be abundant in the dentate gyrus of the human fetus. The subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus is where dividing cells are thought to give rise to new neurons, so the authors looked for the formation of this zone from fetal development into adulthood. To their surprise, they did not observe a proliferative subgranular zone at any age post-birth in humans. The authors report that by early postnatal life in humans, Ki-67+ cells remained distributed throughout the the dentate gyrus, instead of coalescing into an expected subgranular zone that is present in the rodent brain and suggests that neurogenesis is occurring.

The number of Ki-67+ and SOX+ cells declined in the first year of life in humans. Some Ki-67+ cells were still noted through age 35, but the authors note that these cells were distributed throughout the hippocampus (rather than coalesced into a proliferative zone) and also did not express brain lipid binding protein (BLBP(), a marker of neural stem and progenitor cells, suggesting that the remaining Ki-67+ may not be indicative of neurogenesis. They could indicate ongoing genesis of new glial cells, which is known to occur thoughout life.

The number of immature neurons (DCX+ and PSA-NCAM+ cells) also declined sharply after 1 year of age. A few immature cells were noted at 7 and 13 years but only rarely; most neurons appeared mature at this point. For instance, they had a more mature cell body morphology (rounder, larger), showed distinct axons and dendrites, and expressed the mature neuron marker NeuN. Additionally, some DCX+ neurons observed at 13 years of age also expressed the glial markers IBA1 or OLIG2, suggesting that these are not neurons. In adults, the authors report no evidence of young, immature neurons in the hilus or granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus, where they would be expected to be found. As a positive control, they did find a few immature neurons in the ventricular/subventricular zone, a known site of adult neurogenesis.

In contrast to humans, a subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus does appear to form in macaques. However, proliferating and immature cells are also rare by adulthood in these animals. The authors also used BrdU to label recently dividing cells in 1.5-year-old and 7-year-old macaques. At 1.5 years of age, macaques show markers of progenitor cells and young neurons in the subgranular zone, and indeed DCX+BrdU+ and a few NeuN+BrdU+ cells were observed, indicating that neurogenesis is occurring at this age. However, at 7 years of age, there were only a couple of DCX+BrdU+ cells and no NeuN+BrdU+ cells, suggesting that neurogenesis is extremely rare in adulthood in macaques.

A criticism levied against this publication was the inclusion of tissue samples acquired from surgical resections from epilepsy patients, given that epilepsy patients may have profound cellular dysfunction in the hippocampus and thus would not be good representatives of normal neurogenesis. The authors counteract this criticism by pointing out that their findings were consistent across surgical resection and post-mortem adult tissue, and across diverse causes of death. They also point out that young neurons were still found in epilepsy samples from children, suggesting that an epileptic condition does not impair the ability to accurately detect immature neurons.

Boldrini et al.

In contrast to Sorrells et al., Boldrini et al. found that nestin+, DCX+, and Ki-67+ cells in the dentate gyrus did not decline with age (Boldrini et al. observed ages 14-79 years old; Sorrells et al. found that proliferative markers had already dropped to near-undetectable levels by age 14). The authors acknowledge that the population of Ki-67+ cells likely included proliferating cells of non-neuronal lineage, as there were about 10x more Ki-67+ cells than nestin+ and SOX2+ cells. Nevertheless, they ultimately conclude that neurogenesis is abundant in old age at levels equivalent to youth.

SOX2+ cells did decline with age. This finding is suggestive of a decline in QNPs, but the stable expression of Ki-67 and nestin could be indicative of a maintained population of INPs and stable proliferative capacity throughout life. PSA-NCAM+ cells also decreased with age, which the authors interpret to be indicative of declining neuroplasticity as opposed to declining neurogenesis.

Boldrini et al. comment that they are unable to compare their findings to Sorrells et al. because different fixation and staining protocols were used on the tissue, and also Sorrells et al. did not use stereology, the gold standard for cell counting. However, stereology is not possible to conduct on sections with a very few number of cells of interest, as was the case in the tissue from the Sorrells paper. Additionally, Sorrells et al. were still able to detect evidence of neurogenesis in positive controls, including other brain regions and children, supporting the argument that they are not compromising tissue integrity or masking antigens.

Perhaps the primary criticism of the Boldrini paper is that not enough care was taken, using co-labeling techniques, to differentiate proliferating or immature glial cells from neurons. Without knowing the precise cellular fate or identity of proliferating and immature cells, it is difficult to reach a conclusion about adult neurogenesis. For example, Sorrells et al. co-labeled Ki-67 with SOX1 and 2, as well as BLBP. Boldrini et al. did co-label Ki-67 with nestin, but there appear to be more nestin- than nestin+ Ki-67 cells in the representative images (quantification was not provided for double-labeled cells).

Moreno-Jiménez et al.

The fixation process of human tissue is a possible culprit in dicrepancies between studies about the presence or absence of human AHN. This paper used a rigorous methodologial approach to test different fixation procedures, finding that they did in fact have an impact on the number of detectable DCX+ cells. They also have very high-quality stains to show for their rigorous fixing and staining procedures, which lends support to their conclusion that there are immature cells in the dentate gyrus of humans.

They further support this conclusion by showing DCX+ cells in apparent different maturational stages. For instance, they show calretinin+ cells (expressed in less mature neurons) with morphological and spacial characteristics of immaturity. These cells had a smaller cell body, were present in the subgranular zone part of the dentate gyrus (unlike Sorrells et al., this paper reports the presence of a subgranular zone), had a horizontal and slightly elongated morphology (indicative of migration), and multiple neurite processes. In contrast, another population of DCX+ cells expressed calbindin (present in more mature neurons), had a larger cell body area, one pronounced neurite, and were present within the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus, integrating with other mature neurons. These DCX+ cells also doublestain for the mature neuron marker NeuN, helping to support the conclusion that the cells are neurons and not glia. However, both calretinin and calbindin are also expressed in interneurons, making it possible that the DCX cells that co-expressed with calretinin and calbindin may in fact be populations of these interneurons in the dentate gyrus.

Importantly, in this paper there is no analysis for the presence of dividing stem cells or immediate progenitor cells - labeled with Ki-67, for instance. They were also not able to identify DCX+ in brain regions where others have shown DCX+ cells, such as in the entorhinal cortex. Lastly, immature cells in the dentate gyrus may undergo very protracted maturation in humans. Without birthdating of these cells or co-labeling with proliferative markers, it is not possible to tell how recently they were actually born. It is possible that they were born earlier in life, but never fully matured and thus don’t represent newly generated neurons.

Lastly, a criticism of the Sorrells et al. paper that did not find evidence for human AHN was that some of their human samples had a long postmortem delay. However, this paper tested the effect that postmortem delay has on the number of detectable DCX and other cells, and somewhat surprisingly found no relationship between PMD and number of detectable cells, suggesting that may not have interfered with the results of Sorrells et al.

Putting it all together?

The purpose of this post is not to reach a conclusion, or even a personal opinion, on the question adult hippocampal human neurogenesis. More expert research is necessary.

In an excellent review article, Snyder writes that in order to interpret findings about the presence or absence of adult hippocampal neurogenesis across various species, it is necessary to scale findings according to the respective lifespan of each species. For example, more development occurs in utero in humans, whereas more development occurs postnatally in rodents:

Once developmental timing is accounted for, the human and animal literatures are generally consistent with one another: the human hippocampus develops largely prenatally, leaving less opportunity for postnatal neurogenesis. In contrast, the rodent DG forms postnatally and is typically studied in adolescence and young adulthood, when neurogenesis rates remain high.

He also proposes that what some are mistaking for adult neurogenesis in humans may actually be protracted plasticity:

In mice and rats, DCX is primarily expressed for the first 2-3 weeks of neuronal development but in primates it is expressed for at least 6 months. This is a ~10x different in duration, which also approximate the difference in lifespan between primates and rodents. Applying this rule to the critical period for enhanced LTP (~6 weeks), newborn DG neurons might be expected to have enhanced synaptic plasticity for over a year in [non-human] primates and even longer in humans. Similarly, if the enhanced capacity for morphological plasticity, which lasts at least 4 months in rats, is scaled according to human lifespan (30x), DG neurons in humans would be expected to retain this heightened plasticity for at least a decade. The data suggest that even DG neurons born in childhood in humans could retain unique functions in adolescence and adulthood.

Lastly, there are theories proposing that, with increasing evolutionary complexity and brain size, neurogenesis and regenerative capacity in general becomes more limited. Sorrells et al. write: “A lack of neurogenesis in the hippocampus has been suggested for aquatic mammals (dolphins, porpoises and whales), species known for their large brains, longevity and complex behavior.”

There are no answers yet, but the question is fascinating, both from a philosophy of science perspective and from a mental health one, as many neuropsychiatric and neurological diseases, including Alzhemier’s, depression, PTSD, and others, are thought to involve impairments in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. For instance, it is thought that antidepressants work in part by spurring on AHN, as does exercise. Therefore, the question of whether adult hippocampal neurogenesis exists in humans could be of significant consequence for understanding and treating disorders like depression.

References

- Boldrini et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis persists throughout aging. Cell Stem Cell (2018).

- Moreno-Jiménez et al. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Medicine (2019).

- Parker, D. Kuhnian revolutions in neuroscience: the role of tool development. Biol Philos. (2018).

- Snyder, J.S. Recalibrating the relevance of adult neurogenesis. Trends in Neurosciences (2019).

- Sorrells et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature (2018).

Banner Image Credit

Dr. Wutian Wu, University of Hong Kong: Nikon Small World 2016 Photomicrography Competition