Published: Jun 10, 2019 by Chloe

Advances in understanding and treating depression have stalled in the past several decades, until recently. In March of 2019, the FDA approved esketamine, available as a nasal spray, for treatment-resistant depression. This approval signifies a major breakthrough in treating this devastating disorder, as conventional SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) require weeks or months to take effect and patients often undergo years of trial and error before settling on an efficacious medication. Even after this process, many patients still do not respond to SSRIs. By contrast, esketamine can work within hours to provide rapid relieve for depression that is sustained for several weeks before another dose.

What is esketamine?

Ketamine and its variants are antagonists for the NMDA receptor (NMDA-R), an excitatory amino acid receptor that receives the ligand glutamate and increases the probability of neuronal firing. Esketamine (also codified as (S)-ketamine) is the s-enantiomer of ketamine. Ketamine itself is a mixture of two enantiomers, R and S (and is therefore sometimes referred to as (R,S)-ketamine). An enantiomer is one of two versions of a molecule that are mirror images of each other, much like the left and right hand. As an interesting side note, this is where the “R” and “S” nomenclature comes from, with “R” standing for “rectus” (Latin for “right”) and “S” for “sinister” (Latin for “left”). The R and S versions have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms, but differ in the three-dimensional orientations of their atoms in space. These differing orientations can give different the different enantiomers of ketamine different binding affinities for the NMDA receptor. For instance, (S)-ketamine has three- to four-fold higher affinity for the NMDA receptor than (R)-ketamine. This post will focus primarily on (R,S)-ketamine (referred to here as simply “ketamine”) because this compound has been most extensively studied in pre-clinical and clinical trials for depression.

How does ketamine work to relieve depression?

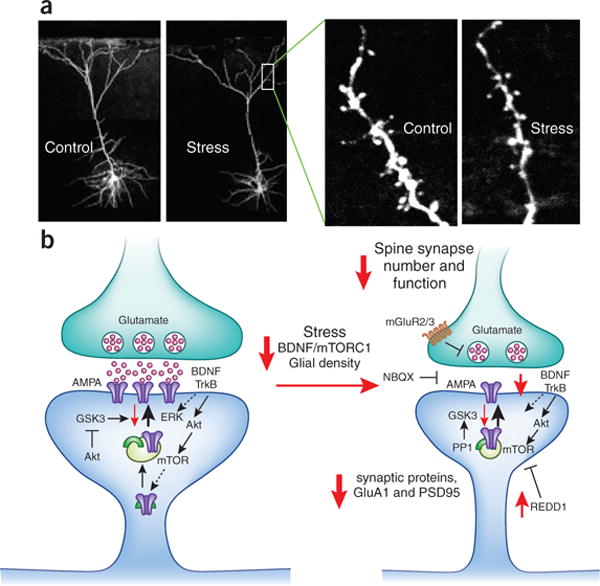

Depression is a complex and heterogeneous disorder involving disturbances in multiple brain regions and networks. The true complexity of depression is still being uncovered, but the disorder is known to involve reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, two interconnected brain regions that are involved in emotional regulation. The dendritic arborization and spine density of excitatory pyramidal cells is also reduced in these brain regions, contributing to the reduction in overall activity and volume. These facets of depression can be produced in animal models of chronic stress, highlighting the fact that chronic stress is a major risk factor for the development of depression and related disorders like anxiety.

This image depicts dendritic spine loss observed in stress and depression. The left side of the figure depicts a healthy dendritic spine. In this spine, glutamate is released from the presynaptic neuron to stimulate AMPA receptors on the postsynaptic side. This also stimulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) acting on TrkB receptors, which activates the ERK and Akt-mTOR cascade to produce new synaptic proteins including more GluA1-containing AMPA receptors (purple) and PSD-95 (green arch symbol) that are required for healthy synaptic functioning. Akt signaling also blocks GSK3, which is something that prevents AMPA receptor insertion into the postsynaptic membrane and dendritic growth.

The right side of the figure represents spines in stress and depression. There are less AMPA receptors in the postsynaptic membrane due to reduced BDNF and downstream signaling. Factors like REDD1 also block mTOR and prevent the synthesis of new synaptic proteins. The overall result is reduced glutamatergic signaling and reduced neuronal excitation in the affected brain regions, namely the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.

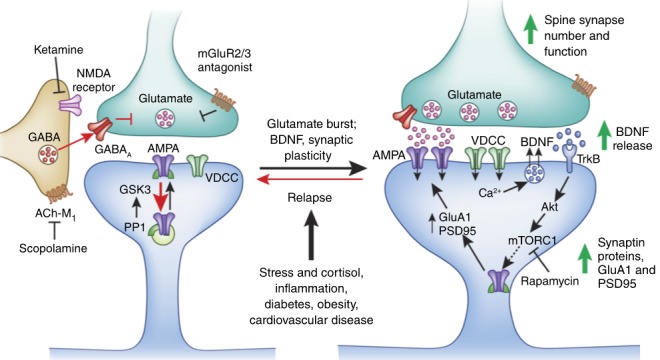

Ketamine is thought to produce a burst of glutamate that increases activity in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus and stimulates signaling pathways that trigger the remodeling of synapses and ultimately restore dendritic arborization and spine density. This description raises two questions. One, an NMDA-R antagonist like ketamine should reduce excitatory neurotransmission through its blockade of a major glutamate receptor, so how does NMDA antagonism produce a paradoxical glutamate burst? Second, what are those downstream signaling pathways that propagate ketamine’s mechanisms of action?

The most widely accepted answer to the first question is that ketamine preferentially blocks NMDA-Rs on inhibitory GABAergic interneurons. Ketamine blocks the ion channel component of the NMDA-R when it is open. As inhibitory neurons are more constitutively active than excitatory ones, their NMDA-Rs are more likely to be open at a given moment and thus provide the space for ketamine to bind and block the channel. Preventing excitation of inhibitory neurons leads to subsequent dis-inhibition of excitatory neurons and thus the release of glutamate.

In answer to the second question, the burst of glutamate triggered by ketamine stimulates AMPA receptors on the post-synaptic membrane of an excitatory synapse. This triggers the activation of voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCC). Calcium is a well known “second messenger” that initiates intracellular signaling cascades following neuronal stimulation. Calcium triggers the release of BDNF which binds to its receptor TrkB, activating Akt signaling pathways that stimulate mTOR to increase the synthesis of proteins required for synapse formation. In this way, the intracellular signaling cascades initiated by ketamine can reverse synapse loss seen in cases of stress and depression. Blocking parts of this signaling cascade (for example, with rapamycin to block mTOR) can prevent the antidepressant effects of ketamine administration.

The diagram above depicts these signaling cascades involved in the mechanisms of ketamine’s antidepressant effects. The diagram also points out two other receptor types that have therapeutic potential in depression: muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (ACh-M) and metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 (mGluR2/3). These are the targets for novel fast-acting antidepressants beyond ketamine.

ACh-M receptors

The ACh-M receptor on inhibitory neurons facilitates the activation of these cells. Therefore, blocking the ACh-M receptor would help reduce inhibitory transmission, dis-inhibiting presynaptic glutamatergic terminals and facilitating glutamate release, much like ketamine blocking NMDA-Rs on inhibitory neurons. Scopolamine is a ACh-M antagonist that has rapid antidepressant effects similar to ketamine.

Presynaptic mGlu2/3 receptors

mGlu2/3 receptors are present on the presynaptic terminal and are inhibitory autoreceptors that reduce glutamate release from an excitatory neuron. Blockage of these inhibitory autoreceptors can also stimulate a glutamate burst similar to ketamine, and activate the downstream signaling cascades described above to alleviate depression.

Selective GluN2B antagonists

Antagonists that selectively inhibit NMDA-Rs that contain the GluN2B subunit also have rapid antidepressant effects, suggesting that GluN2B-containing NMDA-Rs are somehow uniquely involved in the pathology of depression. GluN2B-containing NMDA-Rs are somewhat unique. They are more commonly found in the extra-synaptic membrane, and are not activated by glutamate release directly at the synaptic cleft. Only when glutamate is released in excess, and spills over past the synaptic cleft into extra-synaptic space, are GluN2B-containing NMDA-Rs activated. When activated, these receptors block ERK signaling pathways and prevent surface expression of AMPA receptors. In this way, GluN2B-containing NMDA-Rs may be a fail-safe against excess glutamatergic transmission under healthy conditions and prevent excitotoxicity. In cases of depression, however, pathological activation of GluN2B-containing NMDA-Rs (possibly by stress) prevents dendritic growth. Therefore, selectively blocking these receptors present in the extra-synaptic membrane may lift a block on dendritic growth and thus have rapid antidepressant effects similar to ketamine.

GLYX-13, aka Rapastinel

NMDA-R activation requires glutamate binding as well as glycine, a co-agonist. Rapastinel is a glycine-like agonist of the NMDA-R which surprisingly has rapid antidepressant effects similar to ketamine, but with less side effects. How can rapastinel, an NMDA-R agonist, have effects similar to ketamine, and NMDA-R antagonist? In this case, rapastinel may be facilitating NMDA-R activation directly on excitatory neurons, as opposed to ketamine, which is thought to be acting primarily on inhibitory neurons. In this way rapastinel can increase glutamatergic signaling to activate the downstream signaling cascades that help alleviate depression by promoting spine growth in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.

The role of dopamine

Excitatory neurons are a diverse, heterogeneous class of cell. In the prefrontal cortex, excitatory neurons can be classified according to which dopamine receptor subtype they express, Drd1 or Drd2. While ketamine may impact these Drd1- and Drd2-expressing neurons indiscriminately, the fast-acting antidepressant response may only be driven by one of them. Indeed, a recent study found that selective activation of Drd1-expressing neurons has an antidepressant effect, while activation of Drd2-expression neurons does not. Even more specifically, Drd1-containing neurons that project from the prefrontal cortex to the basolateral amygdala are involved in the antidepressant response. This finding supports evidence that some dopaminergic agents, like aripiprazole (aka Abilify) can augment antidepressent treatment with conventional SSRIs.

Some notes on the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission

Depression involves GABAergic deficits in the PFC and hippocampus. There are numerous reports of reduced GABAergic transmission and reduced expression of GABAergic system markers in these brain regions in humans with depression as well as rodent models of the disorder. This is alongside reduced excitatory transmission. Excitation and inhibition exist in a complex balance with each other, and the relationship between the two systems, as well as the nature of excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) imbalances in depression, is still being unraveled. One of the ways in which excitation and inhibtion can interact with each other is through homeostatic mechanisms. If inhibitory transmission is decreased, excitatory transmission will also decrease in order to maintain balance, and vice versa. In depression, “it has been suggested that decreased GABA function could play a causative role in the reduction of excitatory synapses resulting from chronic unpredictable stress (CUS). This is supported by evidence that partial (30%) ablation of somatostatin neurons [a type of inhibitory neuron] results in compensatory, long-lasting reductions in cortcio-cortical excitatory drive.” Somatostatin (SST) neurons are known to be dysfunctional in depression, so this example illustrates how reduced inhibitory transmission can contribute to reduced excitation, both of which are characteristic of depression.

There are multiple subtypes of inhibitory GABAergic interneurons that complicate the picture. The main two are SST neurons that target the dendrites of excitatory pyramidal cells, and parvalbumin (PV)-expressing neurons that target the cell body. Ablation of NMDA-R on PV cells does not prevent the rapid antidepressant effects of ketamine, but ketamine reduces PV expression, which is necessary for its fast-acting antidepressant effects. This implies that PV is part of ketamine’s antidepressant effects, but this is downstream of NMDA-R antagonism. It is more likely that ketamine antagonizes NMDA-R on SST-expressing interneurons. Scopolamine also exerts its antidepressant effects via Ach-M receptors specifically on SST neurons, alleviating inhibtion at the dendritic level to increase synaptic excitation.

Many questions still remain. For instance, what causes GABAergic deficits in the first place? Also, how does the hypothesis of GABAergic deficits and reduced inhibitory transmission fit with the hypothesis that blocking NMDA-Rs on inhibitory neurons is therapeutic? These are open questions that research in the field is continuing to investigate.

Concluding thoughts

Other novel fast-acting antidepressants are still under investigation. Just to name a few:

- NV-5138: directly stimulates BDNF and mTOR signaling to increase the synthesis of synaptic proteins and promote dendritic growth

- Novel compounds that reduce inhibitory transmission via GABA-A alpha-5 receptors (ex. MRK-016)

- Cannabidiol (CB) acting on CB receptors: CB receptors are located pre-synaptically and their activation resulsts in hyperpolarization and reduces neurotransmitter release. CB receptor activation on inhibitory neurons may dis-inhibit excitatory synapses, similar to ketamine

- (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine, a ketamine metabolite that also exerts its antidepressant effects through BDNF/mTOR signaling

Communcation between inhibitory and excitatory neurons, as well as intracellular signaling cascades that occur within these cells, are extremely complex. The good news is that there appear to be multiple points at which these cells and pathways can be targeted to alleviate depression, and the mechanisms of multiple different types of fast-acting antidepressants all seem to converge on BDNF/mTOR signaling. Hopefully, esketamine is just the beginning of novel breakthroughs for depression treatment that can reach patients who thus far have been unable to experience relief through conventional pharmaceutical methods.

References

- Duman et al. Synaptic plasticity and depression: New insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nature Medicine (2016).

- Duman. The dazzling promise of ketamine. Cerebrum (2018).

- Fogaça and Duman. Cortical GABAergic dysfunction in stress and depression: New insights for therapeutic interventions. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience (2019).

- Gerhard et al. Emerging treatment mechanisms for depression: Focus on glutamate and synaptic plasticity. Drug Discovery Today (2016).

- Ghosal et al. Prefrontal cortex GABAergic deficits and circuit dysfunction in the pathophysiology and treatment of chronic stress and depression. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences (2017).

- Hare and Duman. A medial prefrontal cortex cell type necessary and sufficient for a rapid antidepressant response. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) (2019).

- Kato et al. Sestrin modulator NV-5138 produces rapid antidepressant effects via direct mTORC1 activation. Journal of Clinical Investigation (2019).

- Wohleb et al. GABA interneurons mediate the rapid antidepressant-like effects of scopolamine. The Journal of Clinical Investigation (2016).

- Zhou et al. Loss of phenotype of parvalbumin interneurons in rat prefrontal cortex is involved in antidepressant- and propsychotic-like behaviors following acute and repeated ketamine administration. Molecular Neurobiology (2015).